Wright once asked: “Could words be weapons?” 12 Million Black Voices shows that they definitely could. It is, in fact, a work about the unsung stories and living conditions more hardly felt by the African American communities that suffered extensively during the Great Depression.

In writing in first person plural, Wright’s use of “we” and “us” not only emphasizes a certain collectiveness within itself, but it also makes a point of referring to his “us” as whole, ignoring all further divisions within the group, thus creating a feeling of community and belonging.

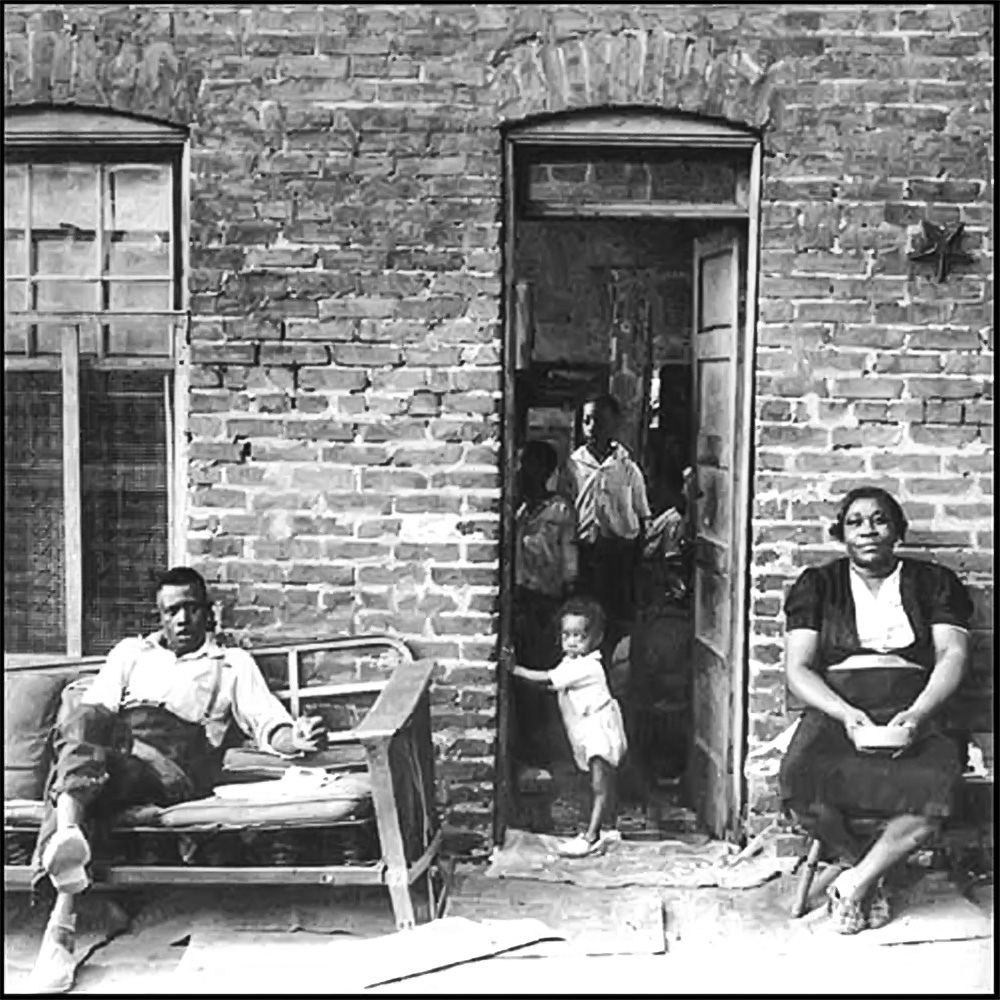

Initially, I thought that the collective voice evoked an air of authenticity, considering that he had combined his words with explicit and self-explanatory photographs that aided the reader in relating to the cause. There is an interesting juxtaposition between his eloquent mode of expression, with his use of words such as “adroitly”, “covenants” and “hence”, and his wide argument of deprivation. Therefore, to what extent are his experience and account of events actually authentic?

Having said this, Margaret Bourke-White writes “Whatever facts a person writes have to be coloured by his prejudice and bias. With a camera, the shutter opens and closes and the only rays that come in to be registered come directly from the object in front of you”. So is objectivity actually possible if photography is involved? Trachtenberg argues that “American photographs are not simple descriptions but constructions, that the history they show is inseparable from the history they enact: a history of photographers employing their medium to make sense of their society”. There are always two sides to one story, and the issue of authenticity has been at the centre of critical debates for centuries. The way in which we analyse objectivity is, in fact, subjective. There is no right or wrong, there is no way of knowing what has been tampered with before being shown to the public, and what has not.

We associate veracity of facts with emotion. 12 Million Black Voices was clearly written for white readership, awakening their consciousness with shocking words, and enforcing those words with images. Edwin Seaver declared on a 1941 radio program: “I know of no other book that brings home as clearly to the white reader what it means to be black in our country”. The issue at hand is that “we”, have become desensitized towards words and pictures as separate entities. Wright’s combination of them, however, is capable of assuming a documentary style that mimics that of a film, therefore it is easier for the reader to relate and intake the emotions behind the words, as they are laid out explicitly in a visual way.